Kingston upon Hull, or just Hull as it is usually called, is a city in Yorkshire on the northern bank of the Humber Estuary.

Hull owes its very being to its proximity to water. During the late 12th century when the monks of Meaux needed a port to export wool from their estates they chose a spot at the junction of the rivers Hull and Humber to build a quay and named it Wyke on Hull.

In the late 13th century when Edward I looked for a port in the north east of England through which he could supply his battling troops in Scotland he acquired Hull which then became known as Kingston (King’s Town) upon the Hull. The king set about enlarging Hull and built an exchange where merchants could buy and sell goods.

Hull’s importance as a port, and in its early years as an arsenal, at one time second only to London’s arsenal, caused walls with battlements and towers to be initiated in 1327, blockhouses on the east bank of the River Hull in 1542 and a citadel, again on the east bank, in 1681. Although all these have long gone, their imprint on the old town along with the subsequent docks, can still be appreciated.

hover background

hover background

The main export from Hull was wool, along with some salt, grain and hides whilst the chief import into Hull was wine together with wood, iron, furs, wax, seeds for oils and pitch. By the early 17th century there was a ship building industry in Hull and by the end of the century trade in goods was booming. This caused problems as River Hull was unable to cope with the volume of traffic and there were problems with it silting up. This eventually resulted in the development of a dozen new docks in the 18th century.

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

Hull has made a significant contribution to the history of steam-propelled vessels with first attempts as early as 1781. The first regular steam-powered boat on the Humber entered service in 1814. Several other small river packets quickly followed, many both built and owned by Pearson’s of Thorne. The Kingston, a wooden paddle steamer, was built in 1821, and was the first sea-going steam vessel to be built locally. She was put into the Hull-London trade. In 1823, the Kingston made her first North Sea voyage to Antwerp, whilst the Prince Frederick, launched at Pearson’s Yard (Thorne), entered service on the Hull-London run. All these craft were owned by Pearson’s under the name of Hull Steam Packet Company, and were managed by Weddle and Brownlow. Thomas Weddle departed for America in 1834 and Brownlow formed a new partnership that year with William Hunt Pearson, son of Richard Pearson (Thorne), to create the firm of Brownlow and Pearson.

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

The Hull Steam Packet Company had enjoyed a clear field in the Hull-London trade for 12 years, but competition grew in the 1833-1837 period, and bigger ships were required to keep up like the 185 feet Victoria launched in June 1837 from Brownlow and Pearson’s Yard on the Humber Bank.

William Hunt Pearson died at the age of 43 in 1854 after suffering from diabetes. The use of the name Hull Steam Packet Company seems to have ceased after Pearson’s death. A number of links were established by marriage between the Pearsons and local mercantile and shipbuilding families. W.H. Pearson’s eldest daughter, Jane Emma Pearson, married in 1868 James Humphrys of Byrne. A new partnership was established in 1868 with his wife’s brother, Frank Henry Pearson (1844-1915), in the form of Humphrys and Pearson, Kingston Iron Works, shipbuilders, engineers and repairers.

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

Humphrys and Pearson, Ltd was situated on the Humber Bank East of the Samuelson’s shipyard (Sammy’s Point). Samuelson’s Shipyard introduced iron shipbuilding in Hull and was later sold to the Humber Iron Works. Humphrys and Pearson’s Patent Slipway is shown on the 1890 Ordinance Survey map on this web page. Its Winding House is all that’s left today.

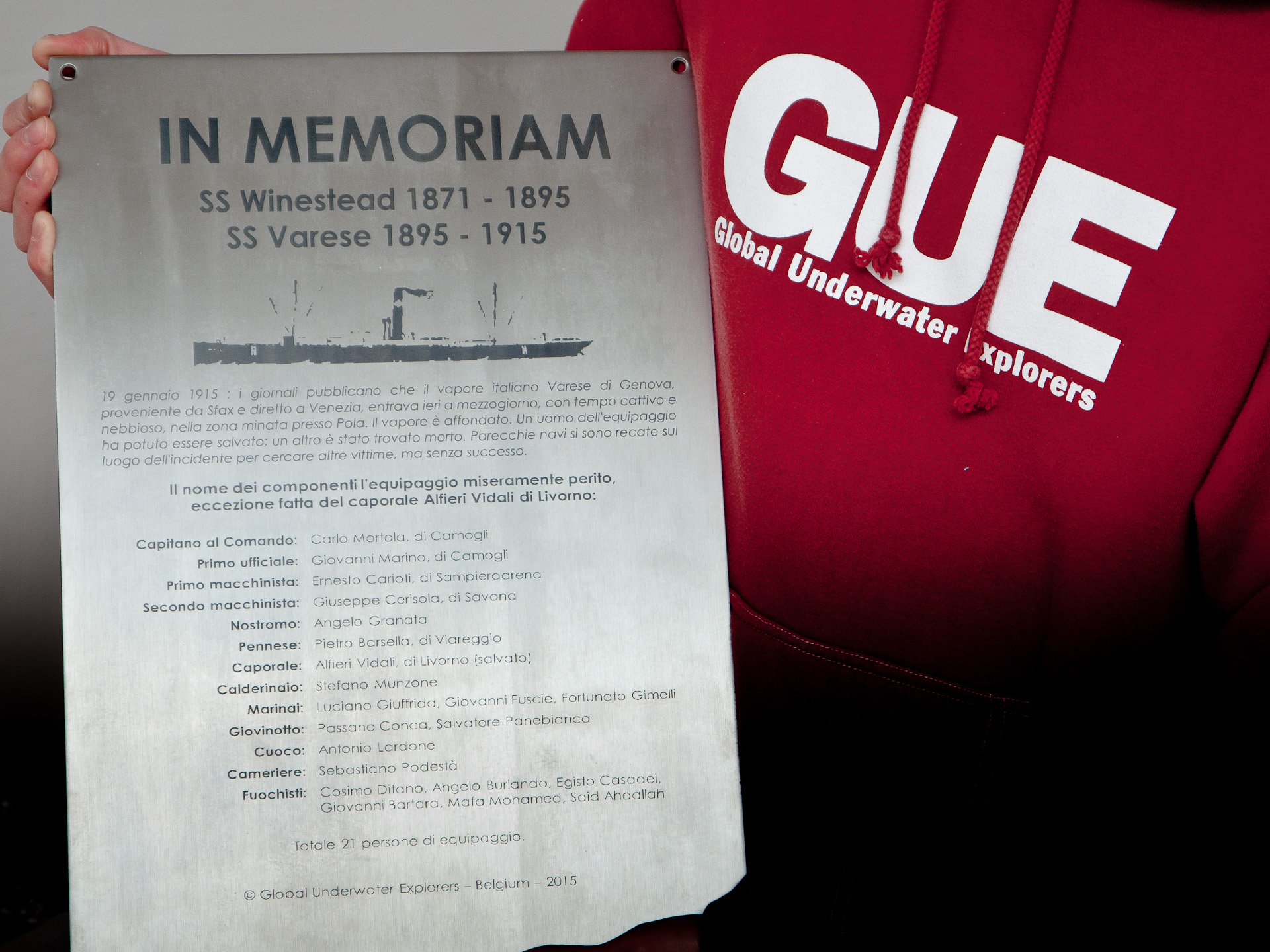

Humphrys & Pearson, Kingston Iron Works, launched 23 ships between 1869 and 1875, including the SS Winestead.

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

Baileys & Leetham, the first owner of the SS Winestead, not only operated a shipping fleet. They also ran the Humber Iron Works and Shipbuilding Co. Ltd in the 1870’s. Looking at the construction records of both Humphrys & Pearson, and Baileys & Leetham, they supplied each other with ships, steam engines and various parts.

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background

hover background